Why faithful Catholics should view post-Vatican II canonisations with suspicion

The flipside to controversial canonisations is of course the controversy surrounding the “non-canonisation” of seemingly deserving candidates.

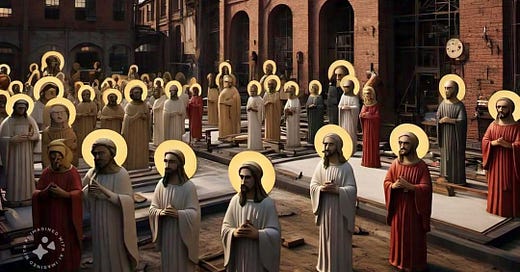

It is alleged that Pope John Paul II canonised more saints than all popes before him combined and this fact alone should cast a shadow of doubt over the legitimacy of the slew of canonisations in the era of the post-conciliar church.

The scepticism that many Traditional Catholics harbour toward saints canonised after the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) emerges from a confluence of theological, liturgical, and ecclesial concerns that arose in the aftermath of the Council's profound changes.

The canonisation of saints—historically viewed as an infallible act of the Church’s Magisterium—has become a point of tension in Traditionalist discourse. This scepticism does not stem from outright rejection of sainthood in general but rather a perceived rupture with past traditions, a dilution of rigor in canonisation processes, and doubts about the theological and moral integrity of some post-conciliar candidates.

To fully grasp this perspective, it is important to first explore the rigorous steps involved in the traditional canonization process, contrast them with the streamlined post-Vatican II process, and then examine specific examples of canonisations that have elicited scepticism.

The Theology of Canonisation

For centuries, the canonisation of saints has been considered a deeply sacred and infallible process within the Catholic Church. A canonised saint is officially recognized as being in Heaven, worthy of public veneration, and a model of holiness for the faithful. Historically, this declaration was treated with utmost seriousness, since it was believed to carry the weight of the Church’s Magisterium under the charism of infallibility.

This understanding is rooted in Christ’s promise to Peter: “Whatsoever you bind on Earth shall be bound in Heaven” (Matthew 16:19). Canonisation, therefore, is viewed as a binding declaration that a soul has attained eternal salvation. To safeguard this extraordinary assertion, the Church developed a process marked by painstaking investigation, theological scrutiny, and a profound sense of caution. Any perceived compromise or lack of rigor in this process raises alarm for Traditionalists, who see such changes as undermining the sanctity and authority of canonisations.

The Steps of the Traditional Canonisation Process

Prior to the reforms introduced in 1983 under Pope John Paul II, the process of canonisation was lengthy, adversarial, and highly juridical. Although there are as many as 20, the key steps involved were as follows:

· Waiting Period

Before a cause for canonisation could even begin, there was a mandatory waiting period of at least 50 years after the candidate’s death. This ensured a cooling-off period, guarding against emotional fervour or premature enthusiasm. The time also allowed the candidate’s virtues and reputation to stand the test of history.

· Opening the Cause and the Role of the Local Bishop

After the waiting period, the local bishop could open the candidate’s cause. This involved gathering witness testimony, writings, and any evidence of the candidate’s heroic virtue and holiness. The process was meticulous, as the bishop needed to ensure there was no hint of heresy, moral failure, or scandal.

· The Role of the Promoter Fidei (Devil’s Advocate)

Central to the traditional process was the role of the promoter fidei, colloquially known as the Devil’s Advocate. This figure was tasked with scrutinizing the candidate’s life and miracles with rigorous scepticism. The Devil’s Advocate posed difficult questions, highlighted any inconsistencies, and presented arguments against canonization. This adversarial approach acted as a safeguard, ensuring that only those of undeniable holiness advanced through the process.

· Verification of Miracles

For a candidate to be declared “Blessed” (beatification), at least two verified miracles attributed to their intercession were required. These miracles had to be of an extraordinary nature (usually physical healings), scientifically inexplicable, and subject to thorough medical and theological investigation. Additional miracles were required for canonisation itself.

· Theological Scrutiny

The candidate’s writings, if any, were reviewed for doctrinal orthodoxy. Any ambiguity, deviation from Catholic teaching, or improper interpretation of Scripture could derail the process. This step was crucial to ensuring that the candidate’s life was not only morally exemplary but also aligned with Catholic doctrine.

· Papal Declaration

After decades—sometimes centuries—of investigation, if all hurdles were cleared, the Pope would issue a formal declaration of canonization, affirming the candidate’s sainthood. By this stage, the Church had subjected the individual’s cause to the most rigorous scrutiny imaginable.

This multi-layered, adversarial process often spanned generations, reflecting the Church’s deep caution and reverence for the declaration of sainthood. Saints canonized through this traditional system, such as St. Thomas Aquinas or St. Pius X, carried with them an unquestioned legitimacy in the eyes of the faithful.

The Post-Vatican II Canonisation Process

In 1983, Pope John Paul II promulgated the apostolic constitution Divinus Perfectionis Magister, which radically reformed the canonization process. The reforms were intended to streamline the process, reduce unnecessary delays, and emphasize collaboration rather than adversarial scrutiny. The key changes include:

· Reduction of the Waiting Period

The mandatory waiting period of 50 years was reduced to just 5 years. In exceptional cases, such as that of Pope John Paul II, even this waiting period has been waived, allowing causes to open almost immediately after death.

· Elimination of the Devil’s Advocate

The role of the promoter fidei was effectively abolished. While the position was replaced by the relator, whose task is to promote thorough investigation, the adversarial nature of the process was lost. Critics argue that this removal eliminates an important safeguard against error or undue enthusiasm.

· Reduction of Required Miracles

The number of verified miracles was reduced: one miracle is now required for beatification, and one additional miracle for canonization. In certain cases, even this requirement has been waived or less rigorously applied.

· Emphasis on Collaboration and Pastoral Sensibilities

The reformed process is more focused on the pastoral significance of a candidate’s holiness. Emphasis is placed on their widespread appeal, social impact, and the "sanctity of ordinary life," rather than the more ascetic and heroic models emphasized in earlier centuries.

· Faster Timeline

The entire process has become significantly faster. Canonisations that once took decades or centuries now often occur within a few years or decades. For instance, Pope John Paul II was canonized just 9 years after his death, while St. Pius X's cause took 40 years.

The Traditionalist Response to the Changes

These reforms can and should be viewed with suspicion for several reasons:

· Perceived Lack of Rigor

Without the Devil’s Advocate, critics argue that the process lacks the necessary scrutiny to challenge the candidate’s life and miracles. This opens the door to candidates being declared saints without sufficient investigation.

· The Haste of Modern Canonizations

The expedited process undermines the Church’s traditional caution, leading to accusations of emotionalism and undue haste. Traditionalist commentator Christopher Ferrara notes:

“The modern Church canonizes individuals with unprecedented speed, often before their legacy can be fully understood. This is a dangerous innovation.”

· Political or Ideological Influences

Traditionalists argue that modern canonizations sometimes reflect a desire to promote certain post-Vatican II reforms. For example, the canonization of Popes John XXIII and Paul VI is seen as implicitly endorsing Vatican II and its controversial outcomes.

· Lowering the Bar for Holiness

The reduction in miracles and emphasis on a “pastoral” model of sanctity raises concerns about whether modern saints meet the same rigorous standards as those canonized in earlier eras.

Controversial Saints and Traditionalist Criticism

While saints canonized in the past were often universally revered, several canonisations after Vatican II have provoked controversy among Traditionalist Catholics. Prominent examples include:

Pope John XXIII

Canonised in 2014 alongside Pope John Paul II, Pope John XXIII’s sainthood is often criticized due to his role in convening the Second Vatican Council. Traditionalists view Vatican II as the catalyst for the Church’s liturgical and theological crises. Critics argue that canonizing John XXIII implicitly endorses the Council’s reforms. Michael Matt, editor of The Remnant, wrote:

“John XXIII is remembered for throwing open the windows of the Church, but many traditional Catholics see only the storm that followed. To canonize him while this storm still rages appears premature at best.”

Pope Paul VI

Pope Paul VI’s canonisation in 2018 stirred significant resistance. He is often criticized for implementing the Novus Ordo Missae (the new Mass) in 1969, which Traditionalists consider a rupture from the traditional Latin Mass. Additionally, Paul VI presided over turbulent years of moral and doctrinal confusion within the Church. Traditionalist writer Peter Kwasniewski remarks:

“Canonising Paul VI raises troubling questions about what standard of sanctity the modern Church is promoting. Can one be considered a saint while presiding over the most visible collapse of Catholic tradition in modern history?”

Pope John Paul II

Canonised in 2014, just nine years after his death, Pope John Paul II remains one of the most controversial modern saints among Traditionalists. While many laud his charisma and global influence, critics highlight his ecumenical actions, particularly the interreligious Assisi gatherings of 1986 and 2002, where non-Christian religions were publicly celebrated. Traditionalists argue such events violate the First Commandment and undermine Catholic doctrine. Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, founder of the Society of St. Pius X (SSPX), criticized John Paul II’s ecumenism, stating:

“Assisi was a scandal for the Church. To place all religions on the same level is to betray the uniqueness of Christ and His Church.”

Mother Teresa of Calcutta

Canonized in 2016, Mother Teresa is revered worldwide for her work with the poor. However, some Traditionalists question the depth of her Catholic witness, pointing to her ecumenical statements and relationships with leaders of other religions. Regarding this much-loved modern Saint, Ferrara wrote:

“Mother Teresa’s charity cannot be denied, but her tendency to equate all religions as pathways to God obscures the Catholic truth: there is no salvation outside the Church.”

Oscar Romero

The canonisation of Archbishop Oscar Romero in 2018 is another example of post-conciliar controversy. While praised for his advocacy for the poor, Traditionalists view Romero as a symbol of the politicization of Catholicism through liberation theology, a movement condemned by the Vatican under John Paul II and Cardinal Ratzinger. His canonisation is a clear endorsement of the Marxist Liberation Theology he was a proponent of.

The flipside to controversial canonisations is of course the controversy surrounding the “non-canonisation” of seemingly deserving candidates such as the following:

1. Pope Pius IX (1792–1878)

Known for proclaiming the dogma of the Immaculate Conception and his strong defense of traditional Catholic teachings amidst modernist influences. He was beatified in 2000 but not yet canonized.

2. Pope Pius XII (1876–1958)

Lauded for his leadership during World War II and his strong stance against communism. Traditionalists view him as a defender of traditional Catholic doctrine, though his canonization has stalled, partly due to historical controversies.

3. Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre (1905–1991)

Founder of the Society of Saint Pius X (SSPX), Lefebvre is a highly polarizing figure. Traditionalists regard him as a champion of pre-Vatican II liturgy and doctrine, though he was excommunicated for ordaining bishops without papal approval. This excommunication is of course highly dubious in itself but a subject for another discussion. Saints Joan of Arc, Mary Mackillop, and Athanasius of Alexandria were all excommunicated at one stage, yet later canonised!

4. G.K. Chesterton (1874–1936)

The English writer, poet, and Catholic apologist is beloved for his wit, orthodoxy, and defense of the faith. Traditionalists often advocate for his canonization due to his strong influence on Catholic thought.

5. Hilaire Belloc (1870–1953)

A Catholic historian, essayist, and writer who vigorously defended the Church against modernist and secularist trends.

6. Queen Isabella I of Castile (1451–1504)

A controversial figure, Isabella was instrumental in the Catholic Reconquista of Spain and supported Christopher Columbus’ voyage. Traditionalists admire her devotion to the faith, though her association with the Spanish Inquisition complicates her cause.

7. Fr. Leonard Feeney (1897–1978)

A Jesuit priest known for his strict interpretation of the doctrine “Extra Ecclesiam Nulla Salus” (Outside the Church, there is no salvation). Though he was initially censured, he remained influential among traditionalists.

8. Venerable Pope Leo XIII (1810–1903)

Famous for his encyclicals defending traditional Catholic social teaching, particularly Rerum Novarum. His canonisation has not progressed despite admiration for his leadership.

9. Miguel Pro (1891–1927)

A Mexican Jesuit priest martyred during the Cristero War. Though he was beatified in 1988, traditionalists often call for his full canonisation as a symbol of resistance to anti-Catholic persecution.

10. Blessed Karl of Austria (1887–1922)

The last Emperor of Austria-Hungary, he sought to rule as a Catholic monarch, promoting peace and Catholic social principles. Though beatified in 2004, some traditionalists believe his sanctity deserves canonisation.

11. Servant of God Fulton J. Sheen (1895–1979)

An influential American bishop and television evangelist whose cause for canonisation has faced delays despite widespread devotion to his legacy.

12. António de Oliveira Salazar (1889–1970)

Prime Minister of Portugal and leader of the Estado Novo regime, Salazar is admired by some traditionalists for upholding Catholic principles in public life.

A Crisis of Sanctity

Traditionalist scepticism towards post-Vatican II canonisations also stems from concerns about a broader dilution of holiness. Saints of previous centuries, such as St. Pius V, St. Alphonsus Liguori, or St. Francis of Assisi, were marked by extraordinary penance, profound asceticism, and uncompromising defence of Catholic doctrine. In contrast, modern canonisations reflect a more lenient understanding of sanctity, one shaped by a spirit of compromise with modern values.

Bishop Athanasius Schneider, a prominent voice within Traditionalist circles, has noted:

“True saints are those who are countercultural. They resist the errors of their time and uphold the Catholic faith without compromise. Many post-conciliar canonizations fail to inspire the same confidence because they lack this clear witness.”

This shift aligns with the Church’s post-conciliar emphasis on mercy and pastoral flexibility at the expense of doctrinal clarity and heroic virtue. The Church has prioritized “kindness” over sanctity, diluting the radical call to holiness that saints once embodied.

The scepticism among Traditionalist Catholics toward saints canonised after Vatican II is rooted in profound unease with the reforms and theological shifts that followed the Council. Their concerns focus on changes to the canonization process, the elevation of controversial figures, and a perceived dilution of sanctity. Saints such as Pope John XXIII, Pope Paul VI, Pope John Paul II, Mother Teresa, and Oscar Romero represent for Traditionalists not only individuals but also symbolic endorsements of a modern Church they believe is in crisis.

While the Church maintains that canonizations are infallible, Traditionalists grapple with the tension between their theological fidelity and their deep concerns about post-conciliar developments. As Peter Kwasniewski aptly summarizes:

“Canonizations are meant to inspire confidence in the Church’s judgment and to present clear models of holiness. When the Church canonizes figures who are embroiled in controversy or represent a break with tradition, she risks undermining her own credibility.”

This justified scepticism reflects a broader crisis of confidence in the Church’s post-Vatican II direction. For faithful Catholics, the canonisation of saints must not only affirm personal holiness but also uphold timeless truth and tradition—a standard that is increasingly compromised in the modern era.

Ave Christus Rex!

Recognise and Resist!

ALSO READ:

The rainbow god vomits on Mother Church – again

A short reflection on Mary and the Immaculate Conception after watching the Netflix betrayal

How the Novus Ordo can shipwreck your faith: "If you hang around a barbershop long enough…"

Update: How you can help Pope Francis convert to Catholicism

The Great Dilemma (Part II): Finding shelter in Traditionalism

This is an excellent summary. The canonization of the "Conciliar" popes (John XXIII thru JP2) cannot be seen as anything but political and ideological. It has been a shameless effort to canonize the modernist V2 itself. No pope after Pius XII could face the scruitiny of a competent devil's advocate. All disregarded our Queen's mandate to consecrate Russia to her Immaculate Heart; all appointed rogue prelates; none upheld the deposit of faith handed down over millenia. Paul IV and JP2 were either hostile to or indifferent to the ancient TLM. A 50 year waiting period on canonizations should be seen as a minimum (e.g. for Padre Pio types) - I'd submit that a century is necessary for popes.

Yes, Agree.

Why do we feel these recent canonizations have the impression were done to garner political ends than declarations of truth?