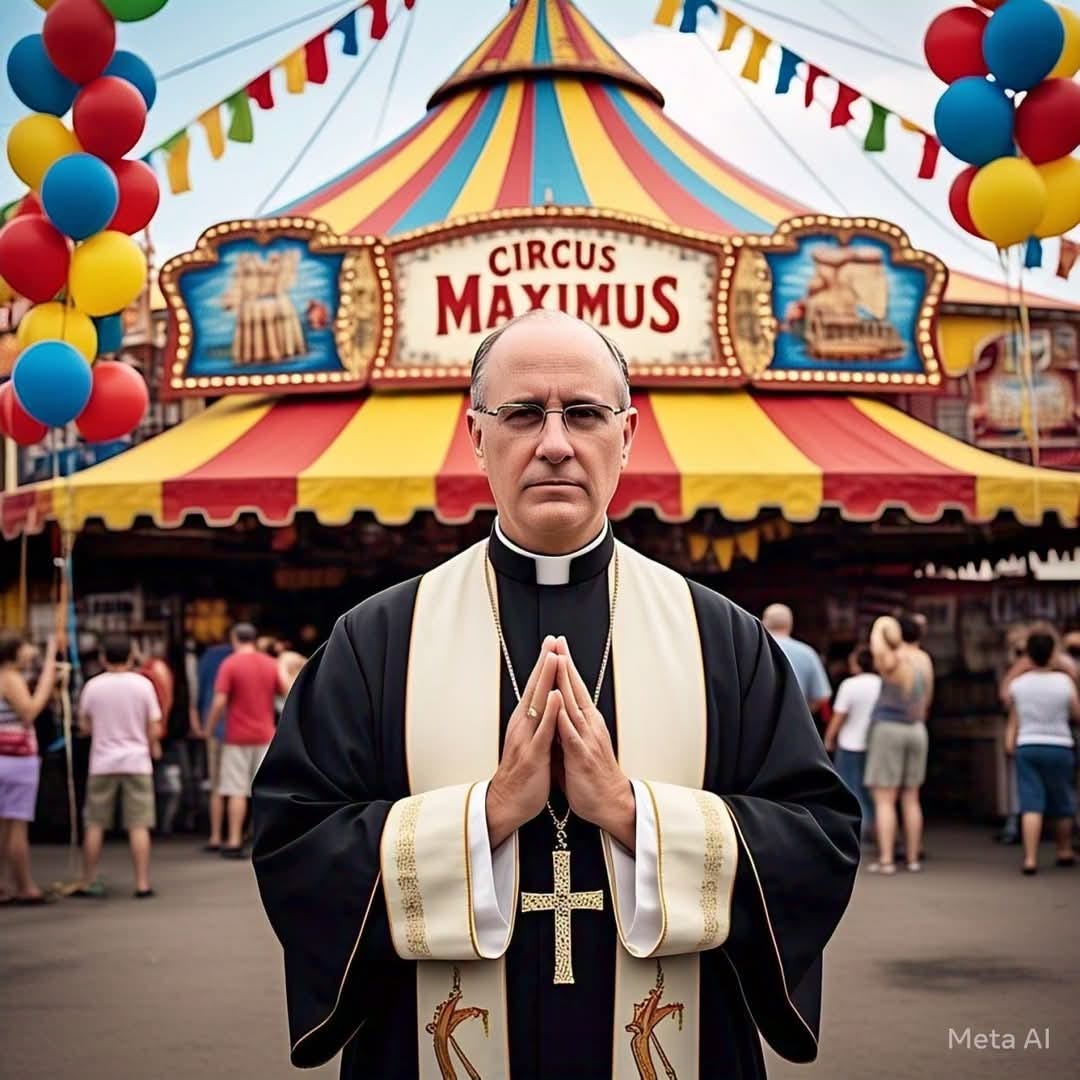

Catholic Church or Modernist Circus – St. Bellarmine settles the argument

Upon examination, it seems that the modern institution, while still using the venerable name “Catholic,” has in fact abandoned the very substance of the faith as revealed in those fifteen marks.

In the annals of Catholic thought, few figures have left as indelible a mark as St. Robert Bellarmine.

Living during the turbulent period of the Counter-Reformation, Bellarmine emerged not only as a formidable apologist of the faith but also as a theologian whose insights into the identity of the Church would echo through the centuries. So much so that in 1931 he was named a Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius XI.

Sadly today — for the modernist, woke, liberal, and progressive contingent in the Church — the fact that this or that Saint is a Doctor of the Church holds little gravitas. (Unless of course this fact could be abused in the promotion of their nefarious agendas).

In his seminal work, De Controversiis, (Volume II, book IV) St. Bellarmine delineated fifteen definitive marks by which the true Church could be recognized. These marks—ranging from the very name that signifies its universality to the miraculous signs that attest to its divine origin—were intended to distinguish the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church founded by Jesus Christ. For generations, these characteristics were seen as living realities in the Church that had faithfully transmitted the faith of the Apostles.

Yet, with the advent of the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) and the ensuing transformation of liturgy, doctrine, and ecclesiology, a profound rupture became apparent.

Upon examination, it seems that the modern institution, while still using the venerable name “Catholic,” has in fact abandoned the very substance of the faith as revealed in those fifteen marks.

But as always, you decide for yourself.

The Name “Catholic”

At the outset, Bellarmine insisted that the true Church must bear the name “Catholic” in its fullest and most ancient sense. This name, he argued, was not a mere label but a testament to the universality and authenticity of the Faith, a title that had been in continuous use since the earliest days of Christendom.

However, today, while the name remains intact, its meaning has been diluted over time. Instead of embodying the steadfast and unchanging truth of the ancient faith, the post-Vatican II Church has embraced an ethos of modernist ecumenism and doctrinal ambiguity. In the pursuit of unity with a broader religious plurality, the Church now engages in dialogue not only with other Christian denominations but also with non-Christian faiths. Such an approach effectively undermines the claim that salvation is found solely within the deposit of faith transmitted by the Apostles.

While previous heresies too claimed the title “Catholic,” it was the preservation of authentic doctrine and practice that set the true Church apart.

In other words, it is not enough to have the word Catholic featured on the wall outside the Church building while inside the building heretical, woke, liberal, and heterodox doctrines are taught, believed, and practiced. This reminds me of Christ’s stark accusation in Matthew 23, “You are like whitewashed tombs, which look beautiful on the outside but on the inside are full of the bones of the dead and everything unclean.”

In this light, the modern institution’s retention of the title appears to be a hollow gesture—a vestige of an ancient identity now lost amid a sea of relativism and compromise.

(On this point, more and more often you will hear phrases such as “Christian community”, “catholic community” or even “St. Johns” sans the word “Church” as if some of the clergy and those in the hierarchy have become allergic to the idea of being seen as the Catholic Church.)

Antiquity

Equally central to Bellarmine’s formulation is the criterion of antiquity. The true Church, he maintained, must trace its origins directly back to the very time of Christ, preserving in its doctrine and liturgy an unbroken continuity with the practices of the Apostles.

Yet in the aftermath of Vatican II, numerous liturgical and theological innovations have raised doubts about this continuity. The introduction of the Novus Ordo Missae, for example, brought about a dramatic reconfiguration of the sacred liturgy. What was once a mystery of sacrifice imbued with centuries of tradition has been reshaped into a form that many critics find reminiscent of modern, even Protestant, worship styles.

This radical departure is not confined merely to liturgical form but extends into the realm of doctrinal interpretation. The Church’s embrace of concepts such as religious liberty and the reorientation toward interfaith dialogue signals a departure from the historic teachings that once underscored the Church’s claim to possess an unaltered and apostolic truth. In abandoning certain elements of its venerable heritage, the modern Church appears to have severed the very link that connected it to the unchanging faith of its founders.

A very recent small but telling example from my sphere of experience was when a priest told young congregants that they should “forget about the Church’s past and rather consecrate on its future and issues such as global warming”.

Duration

A further mark in Bellarmine’s list is the Church’s duration—the requirement that the true Church must endure through all ages without interruption.

While it is an article of faith that the Church, established by Christ, can never be entirely abolished, the question remains as to whether the visible institution that now presides over the faithful is truly the same Church that once safeguarded the apostolic tradition.

History has shown that heresies, such as that of the Arians in the fourth century, have at times temporarily subverted the Church’s mission. In much the same way modernism has infiltrated the hierarchy and reshaped the institution in a manner that betrays its eternal character. It seems a large section of the clergy and hierarchy are intentionally out to destroy, subvert, and pervert Catholic teachings and poorly catechized laity are swallowing the anti-Catholic indoctrination hook, line, and sinker.

Despite the persistence of traditional communities—those who continue to celebrate the pre-Vatican II liturgy and adhere strictly to ancient doctrinal formulations—the mainstream Church, with its extensive apparatus and global influence, now appears as an edifice in which the original spirit has been lost.

In this context, duration is not merely a matter of survival through time but a measure of fidelity to the timeless principles laid down by Christ and His Apostles. Again, merely calling yourself or your “brand” of religion “Catholic” is not enough. You have to ask yourself, is Catholicism taught, believed and practiced in my parish? Or have we fallen for the fallacy that a sign at the gate, a Rosary or two a month and a validly consecrated Eucharist (at the center of a Mass that is probably not pleasing to God) is enough criteria met in order to call myself Catholic?

Amplitude (Universality)

The mark of amplitude, or universality, is another essential element in Bellarmine’s portrait of the true Church. Historically, the Church was envisioned as a universal institution, extending its reach to all nations and peoples without discrimination. Yet the post-Conciliar era has witnessed a marked shift in emphasis from a mission of evangelization to one of dialogue and pluralism.

While the Church remains omnipresent around the globe, its evangelistic zeal has been replaced by a commitment to fostering inter-religious understanding. (I would go so far as to say that the post-conciliar Church and the rabid proponents of its anti-Catholic “dogma” are opposed to evangelization as it will destroy the all-inclusive, non-offending “persona” it worked so hard at creating!)

This approach is antithetical to the biblical mandate to preach the Gospel to all nations. Instead of a fervent missionary impulse, the Church today is perceived as engaging in a kind of cultural accommodation—one that dilutes its claim to possess the fullness of truth by attempting to blend its message with those of other faith traditions.

As a result, the universality of the Church, which once signified an all-encompassing commitment to salvation through Christ alone, has been undermined by the adoption of religious indifferentism and a relativistic outlook.

Apostolic Succession

Closely tied to the notion of universality is the principle of apostolic succession. Bellarmine argued that the true Church must be governed by bishops who could trace their spiritual lineage directly back to the Apostles. This unbroken chain of ordination was seen as a guarantor of the authenticity of the Church’s teaching and sacraments.

However, while the modern hierarchy continues to assert its claim to apostolic succession, numerous changes introduced in the wake of Vatican II have called this claim into question. Reforms in the rite of episcopal consecration and a new ecclesiological emphasis on collegiality have diluted the centrality of the papal office and the clear transmission of apostolic authority.

When bishops begin to espouse moral and doctrinal positions that are in stark contrast to the teachings handed down by the Apostles, the very foundation of apostolic succession is undermined. The authenticity of the spiritual lineage depends not only on a historical chain of ordination but also on the fidelity of those who have been ordained!

In a Church where modern practices have shifted the focus away from strict adherence to traditional teaching, the claim of true apostolic succession is rendered increasingly suspect.

(A little fun anecdote. I personally know a priest who has twice, vehemently in public argued that his hands are not consecrated!)

Agreement in doctrine

Integral to the concept of apostolic succession is the idea that the Church’s doctrine must remain in perfect agreement with the faith of antiquity. For Bellarmine, the teachings of the Church were not subject to change; they were to be transmitted with fidelity to the revelations of Christ and the apostolic witness.

Yet the reforms of Vatican II introduced a series of doctrinal innovations that have led many to conclude that the modern Church has broken with its historical roots. Add to that that many priests just seems to go unchecked in their rogue pursuits of concepts alien to Catholicism, and you realise why you are probably finding yourself in a parish where the priest are supporting female ordination, gay marriage and a host of other issues that is not just not in line with Catholic teaching but directly opposed to it.

The declarations of religious liberty, for instance, seem to contradict the longstanding teaching that salvation is found exclusively within the Church. Similarly, the ecumenical spirit that now characterizes interfaith gatherings and dialogues has diluted the Church’s claim to possess the fullness of truth. When the Church accepts doctrines that run counter to the teachings of past popes and Church Fathers, it creates a disjunction between the present and the past—a discontinuity that casts doubt on its claim to be the eternal depositary of apostolic faith.

Unity

The unity of the Church, both internally among its members and externally with its divinely appointed head, is another mark that Bellarmine deemed indispensable. In the early centuries, unity was achieved through a shared commitment to the unchanging Gospel and a strict adherence to the magisterial tradition.

Today, however, the visible unity of the Church is increasingly compromised by internal divisions and divergent interpretations of key doctrines. The post-Conciliar Church is often characterized by a climate of doctrinal confusion, where differing views on liturgical practices, moral teachings, and even the interpretation of Vatican II’s reforms lead to a fracturing of the once-unified body of believers. This lack of internal cohesion not only undermines the Church’s authority but also raises serious questions about its ability to function as the true Church, which is meant to be a beacon of certainty in a world beset by relativism and moral ambiguity.

Sanctity of Doctrine

The sanctity of doctrine, as outlined by Bellarmine, is another essential characteristic of the true Church. The doctrines of the Church were intended to be holy, guiding the faithful toward a life of virtue and ultimately to eternal salvation.

In the pre-Vatican II era, the Church’s teachings were seen as a pathway to sanctity, producing countless saints and martyrs whose lives bore witness to the transformative power of divine grace. In contrast, the post-Conciliar era has witnessed a decline in the holiness of doctrine.

In place of an unwavering commitment to the Gospel, there is now an emphasis on social justice, environmental concerns, and a kind of humanistic fraternity that, while well-intentioned, tends to obscure the Church’s primary mission of proclaiming the need for repentance, conversion, and the salvific grace of Christ. This shift in focus, they claim, has led to a moral laxity that is evident in the dramatic decline in vocations, mass attendance, and the overall spiritual vitality of the Church.

Efficacy of Doctrine

Closely related to the sanctity of doctrine is the idea that Catholic teaching must be efficacious—that is, it must produce visible fruits in the lives of believers.

Historically, the Church’s doctrine was not merely an abstract set of ideas but a living force that transformed individuals and communities, as evidenced by the innumerable conversions and the blossoming of saints throughout the centuries.

Yet, in the modern era, the fruits of the Church’s teachings seem to have withered. The dramatic decline in religious vocations, the erosion of public morality, and the pervasive sense of spiritual apathy among many Catholics are clear indicators that the new doctrinal formulations are failing to inspire the kind of holy fervor that once defined the Church. The efficacy of doctrine cannot be measured solely by the number of adherents or the size of congregations, but rather by the extent to which the teachings lead souls to the path of true sanctification—a criterion that the modern Church appears increasingly unable to meet.

Holiness of Life

One of the more challenging marks to articulate is the notion of the holiness of the Church’s “founders”, representatives, writers, defenders and the like.

While it is universally acknowledged that Jesus Christ is the true founder of the Church, the traditional view holds that the Church was established in a supernatural manner, imbued with divine guidance and grace. This sanctity of foundation is meant to be mirrored in the subsequent life of the Church, where the spiritual legacy of Christ and the Apostles is carried forward by a community of believers who remain steadfast in the face of modern challenges.

The modern leadership, however, has strayed far from this ideal. In their view, the emphasis on human fraternity, naturalism, and a kind of pastoral sensibility that often appears to prioritize worldly concerns over the transcendent has led to a Church that is, in essence, self-fashioned rather than divinely instituted. The departure from a Christ-centered foundation is a significant indicator that the true spirit of the Church has been compromised.

The Glory of Miracles

Another mark that Bellarmine identified is the glory of miracles—a sign that the Church, as a divinely established institution, is accompanied by supernatural manifestations that confirm its heavenly origin.

In the early centuries, miracles served as powerful attestations of divine favor and played a crucial role in affirming the truth of the Gospel message. Devotions to miraculous apparitions and the veneration of relics were part and parcel of the faithful’s experience of the sacred.

Yet in the modern era, there appears to be a marked decline in the emphasis on miraculous signs. It seems there are “anti-miracle” sentiments, with the goal to demythologise Catholicism and reduce it to nothing more than a naturalistic tool for promoting social justice and other popular “causes”.

Some contemporary leaders have even gone so far as to cast doubt on the authenticity of traditional miracles, such as those associated with Fatima. This retreat from a reliance on the supernatural not only weakens the Church’s claim to a divine origin but also signals a broader trend toward a rationalistic, empiricist worldview that is at odds with the mystical dimension of the faith.

12. The Gift of Prophecy

The gift of prophecy, too, holds a significant place in Bellarmine’s framework. The ability to discern future events through divine guidance was historically regarded as a manifestation of the Church’s close communion with God.

Traditional prophetic warnings—whether delivered through Marian apparitions or the utterances of holy seers—were intended to call the faithful back to the path of righteousness and to forewarn of impending apostasy.

In the modern Church, however, this prophetic dimension appears to have been relegated to the margins. The emphasis on modern theological reinterpretations and the reluctance to acknowledge warnings that have been handed down through tradition suggests that the prophetic gift has been diminished, if not entirely lost, in today’s ecclesial landscape.

In my own experience, those who subscribe to Marian apparitions and the prophecies of Catholic seers and mystics, are shunned as “weirdos”, “superstitious”, “old-fashioned” and a hindrance to the modern “free-thinking” agenda that is being shoved down our throats.

The Confession of Adversaries

The confession of adversaries represents a further mark of the true Church—one in which even those who oppose or critique the institution are compelled, by the weight of divine truth, to acknowledge its authenticity.

In earlier centuries, even the enemies of Catholicism—whether they were secular philosophers, political dissidents, or members of rival religious traditions—could not help but recognize the Church’s authority and the transformative power of its teaching.

Yet in the contemporary era, the modern Church is often lauded by those who once would have condemned it. Secular ideologues, Freemasons, and proponents of globalist ideologies now find common cause with an institution that appears weakened and compromised.

The once-dreaded moral authority of the Church has given way to an image of mediocrity and equivocation, a transformation that is incompatible with the Church’s divine mandate. I am reminded of a quote attributed to Bishop Fulton Sheen that said “People are turning away from Christianity today not because it is too hard but because it is too soft”

The Unhappy end of the Church’s Enemies

In a related vein, the concept of the unhappy end of the Church’s enemies once carried a dual meaning. It was not merely a prediction of divine judgment on those who opposed the Church, but also a statement of the inevitable downfall of any force that seeks to undermine the divine order.

Historically, the perseverance of the true Church in the face of persecution and heresy was a testament to the enduring power of divine grace. Yet today, the internal enemies of the Church—those who, from within, have embraced modern errors and abandoned the foundational teachings—seem to preside over a Church that has lost its moral and spiritual direction.

In this context, the “enemies” are not external but reside within the very leadership of the institution, heralding an internal apostasy that casts doubt on its claim to represent the authentic Church.

The temporal happiness of the Defenders of the Church

Finally, Bellarmine’s last mark—the temporal happiness of the defenders of the Church—offers a vision of divine consolation for those who remain steadfast in defending the true faith.

In earlier times, those who held to the traditional teachings and resisted the encroachments of modernity were often rewarded with spiritual peace and a sense of divine blessing, even in the face of persecution.

Today, however, those who continue to champion the unchanging teachings of the Church frequently find themselves at odds with a modern hierarchy that appears indifferent, if not hostile, to their cause. This my recent battles over orthodoxy has also proven.

Despite the trials and tribulations that come with holding fast to tradition in a rapidly changing world, many traditional Catholics testify to an inner peace that transcends the tumult of contemporary ecclesiastical life—a peace that, in their view, is the true sign of divine favor.

When these fifteen marks are considered in totality, a picture emerges of a Church that once stood as a bastion of eternal truth and unyielding fidelity to its apostolic heritage. St. Robert Bellarmine’s criteria were not arbitrary; they were rooted in a deep conviction that the Church, as instituted by Christ, is marked by certain immutable characteristics that testify to its divine origin.

Yet the post-Conciliar era, with its liturgical reforms, doctrinal shifts, and a marked departure from the ancient paradigms of faith, has left many traditionalists with the impression that the Church’s visible structure has become an unrecognizable shadow of its former self.

The retention of the name “Catholic,” without the accompanying substance of true Catholic doctrine, serves as a stark reminder that a mere title does not guarantee authenticity. Similarly, while the modern Church may claim antiquity in a nominal sense, the profound changes it has undergone have led many to conclude that it no longer possesses the unbroken continuity with the teachings and practices of the Apostles.

The duration of the Church—its ability to persist through the vicissitudes of time—is a testimony to its eternal character. Yet when that duration is marred by internal corruption and a departure from the original mission, it is not enough to assert survival; rather, the Church must demonstrate fidelity to its foundational principles. The amplitude or universality of the Church once meant that its message was proclaimed to all nations, a mission that has now been overshadowed by a preoccupation with interfaith dialogue and an embrace of religious pluralism that dilutes its claim to the fullness of truth. In the same way, apostolic succession, which was once the guarantor of the Church’s authority, now faces serious challenges when the ordained are seen as lacking in the doctrinal rigor and moral fortitude that characterized the early bishops.

Continuity with the doctrinal tradition of antiquity is perhaps one of the most cherished marks of the true Church. The introduction of modern doctrines that seem to stand in direct contradiction to the established teachings of the past raises profound questions about the legitimacy of the post-Conciliar reforms. The internal unity of the Church, once a hallmark of its divine mission, now appears fragmented by divergent interpretations and a crisis of authority that has led to widespread confusion. Moreover, the sanctity and efficacy of doctrine—the very qualities that once led to the production of saints, martyrs, and a vibrant spiritual life—seem to have been eclipsed by modern priorities that favor a kind of social and political accommodation over the uncompromising proclamation of the Gospel.

The holiness of the Church’s founders, manifested in the extraordinary lives of its early martyrs and saints, serves as a beacon for all who claim the mantle of true Catholicism. Yet as modern leadership increasingly appears to fashion the Church in its own image, prioritizing worldly concerns over spiritual imperatives, that divine legacy is at risk of being obscured. Miracles and prophetic gifts, once vibrant signs of the Church’s heavenly mandate, now lie in the background, relegated to relics of a bygone era rather than being recognized as living testimonies of divine intervention. In the modern context, even those who were once compelled by the very weight of divine prophecy seem to have been silenced, their warnings overlooked in favor of an institutional narrative that seeks to downplay the supernatural.

Perhaps most poignantly, the recognition of the true Church by its adversaries—a mark that once inspired both awe and reverence—has been supplanted by a modern consensus that equates compromise with truth. The very forces that once decried the Church’s unyielding commitment to orthodoxy now, in the modern age, find in its softened stance a semblance of validity. Yet this embrace by secular critics is not a testament to the Church’s eternal veracity but rather an indication of its weakened state—a state in which internal adversaries have come to dominate the narrative. The final promise that those who defend the true faith should be endowed with temporal happiness and divine blessing remains, for many, a cause for steadfast resistance against a Church that has lost its way.

In sum, the fifteen marks as expounded by St. Robert Bellarmine serve as both a litmus test and a clarion call—a call to discern whether the institution that bears the name “Catholic” continues to embody the unchanging truth of the Gospel. The post-Conciliar Church, in its fervent pursuit of modernity, has made choices that many view as a departure from the timeless principles that once defined it. The retention of an ancient title, the semblance of antiquity, and the outward structures of continuity are no longer sufficient if the underlying substance has been transformed beyond recognition. When liturgy, doctrine, and ecclesiology are reshaped to meet the demands of a modern world, the risk is that the Church, rather than serving as a steadfast guardian of divine truth, becomes a mutable institution swayed by the tides of cultural relativism.

This is not merely an academic debate; it is a matter of profound spiritual consequence. The true Church, as defined by Bellarmine’s fifteen marks, is more than a historical artifact—it is the living body of Christ, endowed with the mission of leading souls to eternal salvation. When the visible institution fails to embody the sanctity, efficacy, and divine authority that were once its hallmarks, the faithful are left with a stark choice: to remain within a structure that has, in many respects, lost its way, or to cling to the traditions that have been preserved by a resolute remnant.

I will once again conclude with the same St. Athanasius quote which I have used here often before:

“They have the buildings, but we have the Faith.”

Ave Christus Rex!

Recognise & Resist!

ALSO READ:

Beyond the “Early Church Received in the Hand” argument and that St. Cyril quote

A letter to my neo-Protestant “Catholic” friend – Why tradition and orthodoxy matter

The Blessed Virgin Mary and the Crescent Moon of Islam

You have been a bad, bad pope… but how bad?

A beginner’s guide to problems with the Second Vatican Council

Playing Church Destruction Bingo with a mythical Masonic document

I can see that you’re trying to get onto the right path but haven’t yet put all the pieces together. It is easier for me as I haven’t got a lot to unlearn as you probably do.

I’d like to suggest www.wmreview.org and https://crisisinthechurch.com as good sources of information where you can find more answers.

I am of the opinion that the NOM created a schismatic church of a totally new religion.