Why do Some Traditional Catholics Think They Can Dine at the Table of Devils?

The Catholic faith does not require supplementation from the occult arts, it possesses within Scripture, Tradition, and the sacramental life everything necessary for sanctity and salvation.

I am going to begin this piece with a somewhat unusual caveat: although I intend to argue against the popularity of a written work with a very dubious pedigree, I must admit that I have not read it myself.

That is one of the reasons I framed the title of this essay as a question. I am sincerely baffled as to why a work with heavy occult overtones—and the potential to lead readers into dangerous territory—is being promoted by people who otherwise appear to be well-intentioned. I strongly doubt that I will be persuaded of the book’s legitimacy as something Traditional Catholics should incorporate into their spiritual lives, much less promote publicly. However, I hope that by the end of this essay you will at least be convinced as to why this work ought to be avoided and be weary of those Catholic “personalities” who promote it.

I would also like to address the objection that having not read the book disqualifies me from commenting on it. We live in an age where one can access sufficient reliable information about a subject to make a prudent judgment. I do not need to read the works of Aleister Crowley to know that they are satanic.

Before I reveal which work I am referring to, let me first explain why I felt compelled to engage with this subject at all—especially since the esteemed Chris Jackson already addressed it quite comprehensively in a series of articles on his Substack last year.

Earlier this week, while scrolling through Facebook, a post by a reasonably well-known “traditional” Catholic appeared in my feed. I do not follow him on Facebook, though I do follow him on YouTube—albeit not religiously. He has generally struck me as one of the “good guys,” and from time to time I have enjoyed listening to his commentary on the latest ecclesial scandals. He also seemed fairly adept, whether intentionally or not, at acting as a bridge between Novus Ordo Catholics and Traditional Catholicism. That said, I was certainly not a regular viewer of his content.

I was therefore quite surprised when this particular post appeared. At first, I was simply confused. The post contained two photographs of book covers bearing the title Die Grossen Arcana des Tarot. The word tarot immediately caught my attention.

The caption read:

“The 1983 edition that Cardinal Hans Urs von Balthasar gifted to John Paul II. The German edition is formatted differently from the English edition that was published by Catholic publisher Angelico Press.”

I knew who Von Balthasar was, and I knew who John Paul II was. I am not a fan of either. Still, I was surprised to learn that the book in question had been published in English under the title Meditations on the Tarot: A Journey into Christian Hermeticism. The author? Valentin Tomberg—a former occultist who later converted to Catholicism.

I was not especially surprised that a modernist theologian would gift such a book to a modernist “pope.” What did surprise me was that this “traditional” Catholic personality—with roughly 64,000 YouTube subscribers—was publicly posting about it. Initially, I assumed he was criticizing the book. However, as I read through the comments, I realized that he was in fact a strong supporter of it and was actively defending it.

In the comment section, the Catholic “personality” in question wrote that one should “not judge the book by the cover,” and claimed that the book “has drawn many to the Catholic faith over the years.” He also encouraged commenters to check out a “whole channel about it” run by another former occultist turned Catholic, Roger Buck.

Other commenters added remarks such as “very nice,” “this book helped bring me back to the One True Faith,” and similar defenses of the work. Good for them, I guess.

I found it deeply perplexing that Catholics of a more traditional—or at least conservative—persuasion would defend a book that does not criticize the Tarot as a dangerous occult practice, but instead uses it as its very foundation.

I expressed this perplexity in the comment section but received no reply, even though the individual in question responded to others.

In this essay, I want to explain why I find it both dangerous and heartbreaking that not only this gentleman, but other even more prominent “Traditional” figures promote this book and similar occult-derived titles as compatible with the Catholic faith. (Here I am not referring to the Bogus Ordo religion, where anything goes anyway.)

From the outset I want to make it clear that for those Catholics among us, whose spiritual sensibility is shaped by doctrinal clarity, ascetical discipline, and obedience to the Church’s perennial wisdom, this work doesn’t only call for sober and careful discernment but should be avoided altogether for the reasons I am about to explain.

The danger of Meditations on the Tarot does not lie in overt heresy or explicit rejection of Catholic dogma, but rather in its method, its sources, and its underlying worldview.

The book employs the Tarot as a spiritual framework, draws heavily upon Hermetic philosophy, and expresses admiration for occult and heterodox thinkers whose systems are fundamentally incompatible with Catholic faith. These elements, taken together, create a subtle but real risk of doctrinal confusion, spiritual imprudence, syncretism, and possibility to cause scandal.

But Who Was Valentin Tomberg?

Any serious evaluation of Meditations on the Tarot must begin with an honest consideration of its author. Valentin Tomberg (1900–1973) was not a theologian formed within the life of the Catholic Church, nor a product of her spiritual or intellectual tradition. Rather, he was a man whose spiritual journey moved through several esoteric and heterodox systems before culminating, late in life, in a personal conversion to Roman Catholicism. This complex background is essential for understanding both the strengths and the dangers of his work.

Born in Estonia to a Lutheran family, Tomberg became deeply involved in esoteric spirituality as a young man. Most significantly, he was a committed follower of Rudolf Steiner and an active participant in Anthroposophy, a movement explicitly grounded in occult cosmology, clairvoyance, reincarnation, and spiritual evolution. Tomberg worked for years within this system, producing writings and lectures that assumed its worldview and methods. His early intellectual formation, therefore, was not Christian in the Catholic sense, but Hermetic and Gnostic in orientation, emphasizing inner illumination and spiritual knowledge over sacramental life and ecclesial authority.

During the upheavals of the Second World War, Tomberg gradually distanced himself from Anthroposophy. Over time, he became increasingly drawn to Christianity and eventually entered the Catholic Church. This conversion is often cited by admirers as evidence of his orthodoxy. However, conversion alone does not automatically purify one’s intellectual framework, especially when earlier systems are not decisively renounced but instead reinterpreted.

Tomberg did not abandon Hermeticism after his conversion; rather, he sought to reconcile it with Catholicism. He believed that Hermetic philosophy and esoteric symbolism could serve as a kind of preparatory wisdom, illuminating Christianity from within. This conviction underlies Meditations on the Tarot, which he described as an expression of “Christian Hermeticism.” The phrase itself signals a synthesis that the Church has never endorsed and has historically viewed with suspicion.

Importantly, Meditations on the Tarot was written after Tomberg’s conversion, yet it retains the conceptual habits of his earlier esoteric formation. The Tarot is treated not as a cultural artifact to be critiqued, but as a legitimate symbolic language for spiritual contemplation. Occult figures such as Éliphas Lévi and Rudolf Steiner are not rejected as errors of the past, but engaged respectfully as bearers of insight. This continuity suggests that Tomberg’s Catholicism, while sincere, remained filtered through a Hermetic lens.

It is also significant that Tomberg chose to publish his most influential work anonymously. While sometimes interpreted as humility, this anonymity also shielded the work from immediate theological scrutiny and ecclesial accountability. The book carries no imprimatur and was never formally approved as a Catholic spiritual text.

For Traditional Catholics, then, Valentin Tomberg must be understood neither as a Catholic mystic in the classical sense nor as a neutral philosopher. He was a convert whose thought represents an unresolved tension between Catholic doctrine and esoteric speculation. Recognizing this tension is not an act of judgment against his soul, but a necessary step in exercising prudence toward his writings.

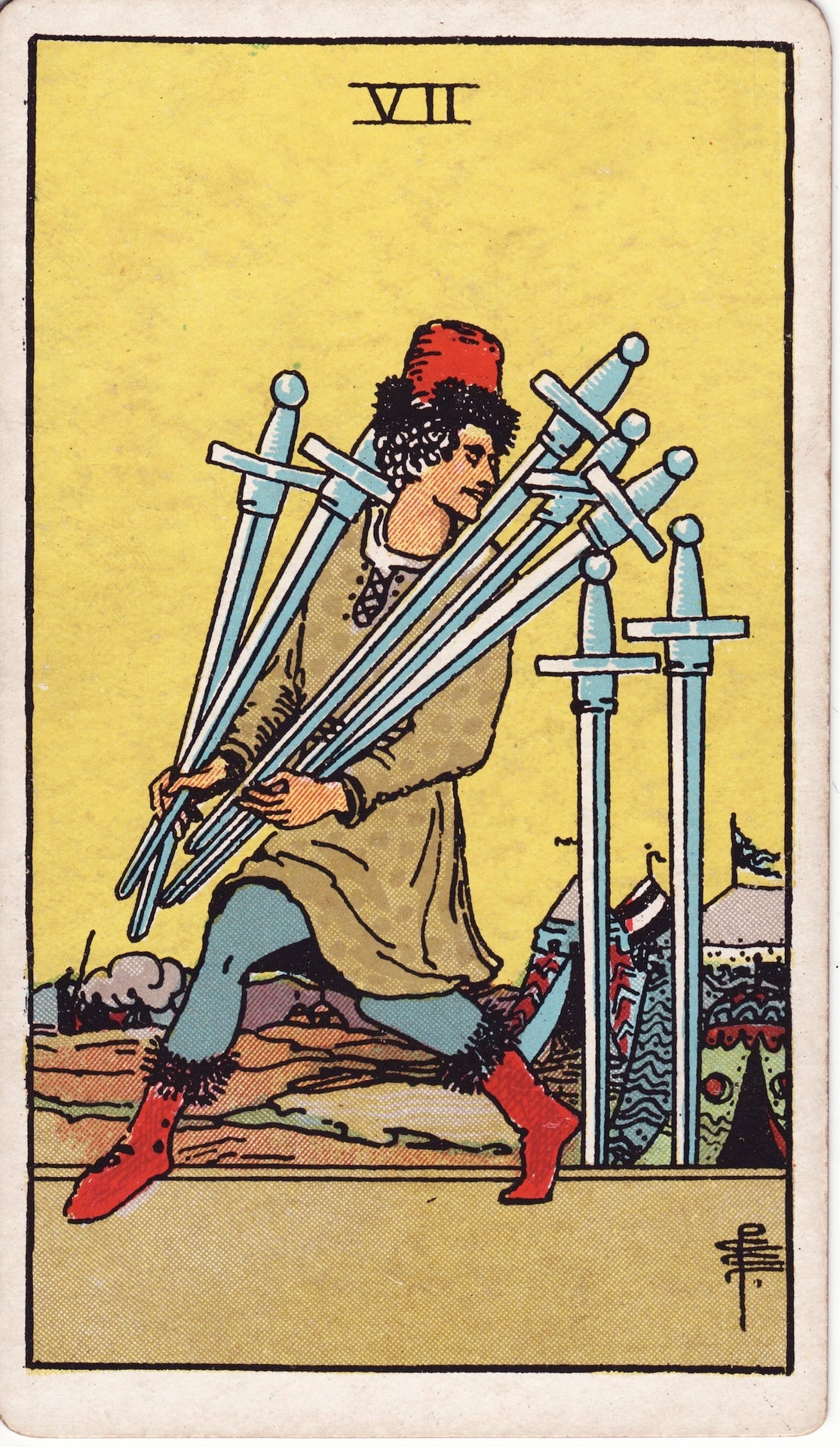

The Nature and History of the Tarot

The Tarot originated in Europe during the late Middle Ages, most likely in fifteenth-century Italy, where it began as a card game used for entertainment among the nobility. These early decks included what later came to be known as the Major Arcana: symbolic figures such as the Magician, the High Priestess, Death, and the Devil. At this stage, the Tarot had no explicit esoteric or divinatory function.

However, beginning in the eighteenth century, a decisive transformation occurred. Enlightenment-era occultists, particularly in France, began to reinterpret the Tarot as a repository of ancient, hidden wisdom. Figures such as Antoine Court de Gébelin claimed—without historical evidence—that the Tarot preserved secret Egyptian mysteries. This speculative mythmaking laid the groundwork for the Tarot’s adoption into Western esotericism.

By the nineteenth century, occultists such as Éliphas Lévi, Papus, and later members of secret societies like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, had fully integrated the Tarot into systems of ceremonial magic, Kabbalah, astrology, and divination. The cards were no longer merely symbolic images but were treated as keys to cosmic forces, spiritual hierarchies, and hidden laws governing the universe. Tarot reading became a means of accessing spiritual knowledge apart from divine revelation.

It is within this esoteric context, not the medieval card game, that the Tarot acquired its enduring and diabolical identity. Today, Tarot is inseparable from occult practice in both theory and popular understanding. Even when stripped of explicit fortune-telling, its symbolic system remains embedded in a worldview that assumes hidden spiritual correspondences accessible through esoteric insight.

The Catholic Church has consistently rejected such practices. Sacred Scripture condemns divination and occult inquiry repeatedly, and the Catholic Church teaches that all forms of divination, including those that appeal to symbolic or psychological explanations, contradict the virtue of religion. This rejection is not based on superstition or fear, but on a clear theological principle: God has revealed Himself definitively in Christ, and man is not to seek hidden knowledge through alternative spiritual systems.

It is therefore not sufficient to claim, as Valentin Tomberg does, that the Tarot can be “redeemed” by symbolic reinterpretation. The very act of adopting it as a spiritual framework risks importing its occult assumptions into Christian contemplation.

Hermeticism’s Origins and Worldview

Closely connected to the Tarot is Hermeticism, the philosophical and spiritual tradition that provides the conceptual backbone of Meditations on the Tarot. Hermeticism takes its name from Hermes Trismegistus, a legendary figure associated with a body of texts known as the Corpus Hermeticum, written in the early centuries of the Christian era. These writings combine elements of Greek philosophy, Egyptian religion, and mystical speculation.

At its core, Hermeticism proposes that divine knowledge is accessible through inner illumination, symbolic understanding, and the realization of hidden correspondences between the human soul (the microcosm) and the universe (the macrocosm). It teaches that man can ascend spiritually through knowledge, awakening to his divine origin and destiny.

While Hermeticism often uses religious language, it is fundamentally a gnostic system. Salvation or enlightenment is achieved not through grace, sacrament, or obedience to divine revelation, but through insight, initiation, and intellectual-spiritual awakening. This worldview has profoundly influenced alchemy, astrology, Kabbalah, ceremonial magic, and modern occultism.

From a Catholic perspective, Hermeticism is not merely incomplete or neutral; it is fundamentally incompatible with the Gospel. Catholicism teaches that man is saved not by secret knowledge but by the redemptive work of Christ, applied through the sacraments of the Church. Grace is a gift, not an achievement that is uncovered through esoteric effort.

Moreover, Hermeticism undermines the distinction between Creator and creature by emphasizing divine immanence at the expense of transcendence. The human soul is often portrayed as divine by nature, requiring awakening rather than redemption. This stands in direct opposition to Catholic anthropology, which affirms that man is created, fallen, and in need of salvation through Christ alone.

The Incompatibility of Hermeticism with Catholicism

The Church has long recognized the dangers posed by Hermetic and Gnostic tendencies. The early Church Fathers vigorously opposed Gnostic sects because they claimed access to higher spiritual knowledge beyond the apostolic faith. Throughout history, whenever such tendencies have resurfaced, the Church has responded with doctrinal clarity.

Hermeticism’s emphasis on symbolic systems, cosmic laws, and spiritual hierarchies accessible through contemplation may appear intellectually attractive, but it subtly shifts authority away from the Church and toward the individual interpreter. The Magisterium, the sacraments, and objective doctrine are replaced by personal insight and speculative synthesis.

This is one of the most daunting dangers present in Meditations on the Tarot. Tomberg does not present Hermeticism as an error that needs be corrected, but as a wisdom tradition to be harmonized with Christianity. He attempts to “Christianize” Hermetic concepts rather than subject them fully to the judgment of the Church. In doing so, he reverses the proper hierarchy between revelation and philosophy.

Occult Authorities and Spiritual Admiration

This methodological error is reinforced by Tomberg’s admiration for explicitly occult figures. Throughout the work, he engages respectfully—and at times reverently—with thinkers such as Éliphas Lévi, Papus, Rudolf Steiner, Jacob Boehme, Madame Blavatsky, Paracelsus, and even elements of Theosophical thought. These figures are not treated merely as historical curiosities by Tomberg, but as sources of genuine spiritual insight.

From where I am sitting, this is deeply problematic. While the Church acknowledges that truth can be found outside her visible boundaries, she also insists that systems rooted in magic, reincarnation, esoteric initiation, or pantheistic cosmology are spiritually dangerous. To praise such figures without strong and explicit correction risks conferring upon them an authority they do not deserve.

A good example of a very troubling character in Tomberg’s work, is Rudolf Steiner, whose Anthroposophy explicitly rejects Catholic dogma in favor of clairvoyant “spiritual science.” Steiner’s influence introduces ideas of spiritual evolution and reincarnation that cannot be reconciled with Catholic teaching, no matter how poetically reinterpreted.

The Spiritual Risks

The greatest danger of Meditations on the Tarot lies in what it relativizes. Catholic doctrine may still be affirmed verbally, but it is placed alongside esoteric systems as one symbolic language among many. The reader is encouraged to admire synthesis rather than submission and obedience.

For Traditional Catholics, whose spiritual formation emphasizes humility, authority, and continuity with tradition, this poses a real threat. Authentic Catholic mysticism is never autonomous. The saints consistently warned against private spiritual exploration detached from sacramental life and ecclesial oversight. Interior illumination, when genuine, deepens obedience and does not replace it.

As the (Traditional) Catholic Faith finds itself under a multi-pronged assault—from the secular world, from the enemies of Christ within Rome, and even from elements within its own ranks (the so-called Trad Inc)—one must also ask another fundamental question: do we really need to associate ourselves with spiritually ambiguous works and devotional practices such as Meditations on the Tarot? Especially since a large part of our fight is for orthodoxy and purity of doctrine and dogma. Wouldn’t this make us look selective about where and when we want the Traditional Faith to be pure? And how would Christ regard this? What of the Saints? The Martyrs? And those who might have been won over to the Truth?

There is also the very real danger of causing scandal and offense. Sacred Scripture warns us with unmistakable severity:

“He that shall scandalize one of these little ones that believe in me, it were better for him that a millstone should be hanged about his neck, and that he should be drowned in the depth of the sea. Woe to the world because of scandals. For it must needs be that scandals come: but nevertheless, woe to that man by whom the scandal cometh.” (Matthew 18:6)

Scripture further issues stern warnings against any form of dabbling in the darkness by those who profess the Catholic faith:

“You cannot drink the chalice of the Lord, and the chalice of devils: you cannot be partakers of the table of the Lord, and of the table of devils.” (1 Corinthians 10:21)

and again:

“What concord hath Christ with Belial? Or what part hath the faithful with the unbeliever? And what agreement hath the temple of God with idols? For you are the temple of the living God; as God saith: I will dwell in them, and walk among them; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people. Wherefore, go out from among them, and be ye separate, saith the Lord, and touch not the unclean thing.” (2 Corinthians 6:15–17)

Finally—and here I must acknowledge that this is a personal observation rather than an empirically demonstrable claim—many of the defenses of this work seem to carry the unmistakable air of an “inner-circle mentality.” There is often a haughty implication that those who promote the book are spiritually advanced initiates who can safely handle material of an occult nature, while those who object are merely timid, prudish, or spiritually immature.

I may be mistaken, but whenever I encounter individuals or groups attempting to justify their involvement in quasi-occult, quasi-Catholic endeavors, they exhibit a mindset strikingly similar to that of Freemasons who dismiss the charge that Masonry is incompatible with Christianity.

All this being said, I realize I have opened myself up to an attack from men of greater intellectual prowess than myself. But we are all watchmen—our brothers’ and sisters’ keepers—and the little guardian angel in my gut tells me I should warn others, lest the sword come and I find myself with the blood of innocents on my hands.

To conclude, I will admit that Meditations on the Tarot seems to be an intellectually impressive and spiritually ambitious work, but ambition should not be conflated with holiness and truth. The Catholic faith does not require supplementation from Tarot symbolism or Hermetic philosophy.

It possesses within Scripture, Tradition, and the sacramental life everything necessary for sanctity and salvation.

Our Lady, Co-redemptrix, pray for us…

Our Lady, Mediatrix of all Graces, pray for us…

Viva Christo Rey!

Also Read:

Did Gänswein Recently Suffer a Concussion?

The Synodal Religion’s Most Dangerous Denial

Ten Reasons Why Cardinal Roche’s Document is Only Good for Lining Your Parrot Cage With

With thousands of writings available through the Internet and many free, why would a Catholic be interested in wasting time reading anything that has to do with the occult except to know how seriously dangerous it is to one's soul? Better we delve into Sacred Scripture, the writings of the Fathers of the Church, St. Thomas Aquinas, the saints and holy men, women and popes.

The most recent Exorcist Files episode is about a possession resulting from a tourist having gotten a tarot card reading on a lark while vacationing in New Orleans.