Dear Hierarchy, Ramadan and Lent Are Not the Same and Catholics Do Not Worship the Same God as Muslims!

This notion is not only misleading but fundamentally contrary to Catholic teaching.

In recent years, the push for “interreligious dialogue” has led many to emphasize superficial similarities between the sacred practices of Christianity and Islam.

A recent Vatican News article even went so far as to compare Ramadan—a month-long period of fasting and reflection for Muslims—to Lent, the Catholic season of penance and preparation for Easter. In the article, Mustafa Cenap Aydin, director of the Tiber Institute Center for Dialogue, suggested that Ramadan and Lent are spiritually akin, uniting Muslims and Catholics in a shared journey of faith. The article even describes these observances as “two brothers, the sons of Abraham, walking together for different reasons.”

This assertion reflects a broader movement within certain circles of the Church that seeks to blur the profound theological differences between Catholicism and Islam under the guise of “interreligious dialogue.” In reality, such efforts serve only to advance the agenda of a false, globalized religion—a distortion of true faith masquerading as ecumenism.

A few days after the Vatican News article appeared, Spanish Catholic news outlet InfoVaticana also reported that “On the occasion of the beginning of the month of Ramadan, the Catholic Church in Spain sent - a message of fraternity to the country's Muslim community, expressing its best wishes that this sacred time bear fruits of prayer, fasting and charity” and said that “the statement, signed by Mgr. Ramón Valdivia Giménez, president of the Episcopal Sub-Commission for Interfaith Relations and Interreligious Dialogue, and Rafael Vázquez Jiménez, director of the Secretariat, underlines the values shared between Christians and Muslims in this time of spiritual reflection. This time of Ramadan and that of Lent for Christians are intended to make us grow in intimacy with God through prayer, fasting and charity, the message points out, establishing a parallel between the two religious traditions”.

In other words, the Church is officially confirming those who reject Christ and are lost in their sinful and erroneous ways, instead of trying to bring them to the truth and light of Christ.

Worse still, some have taken this comparison a step further, arguing that Catholics and Muslims worship the same God. This notion is not only misleading but fundamentally contrary to Catholic teaching.

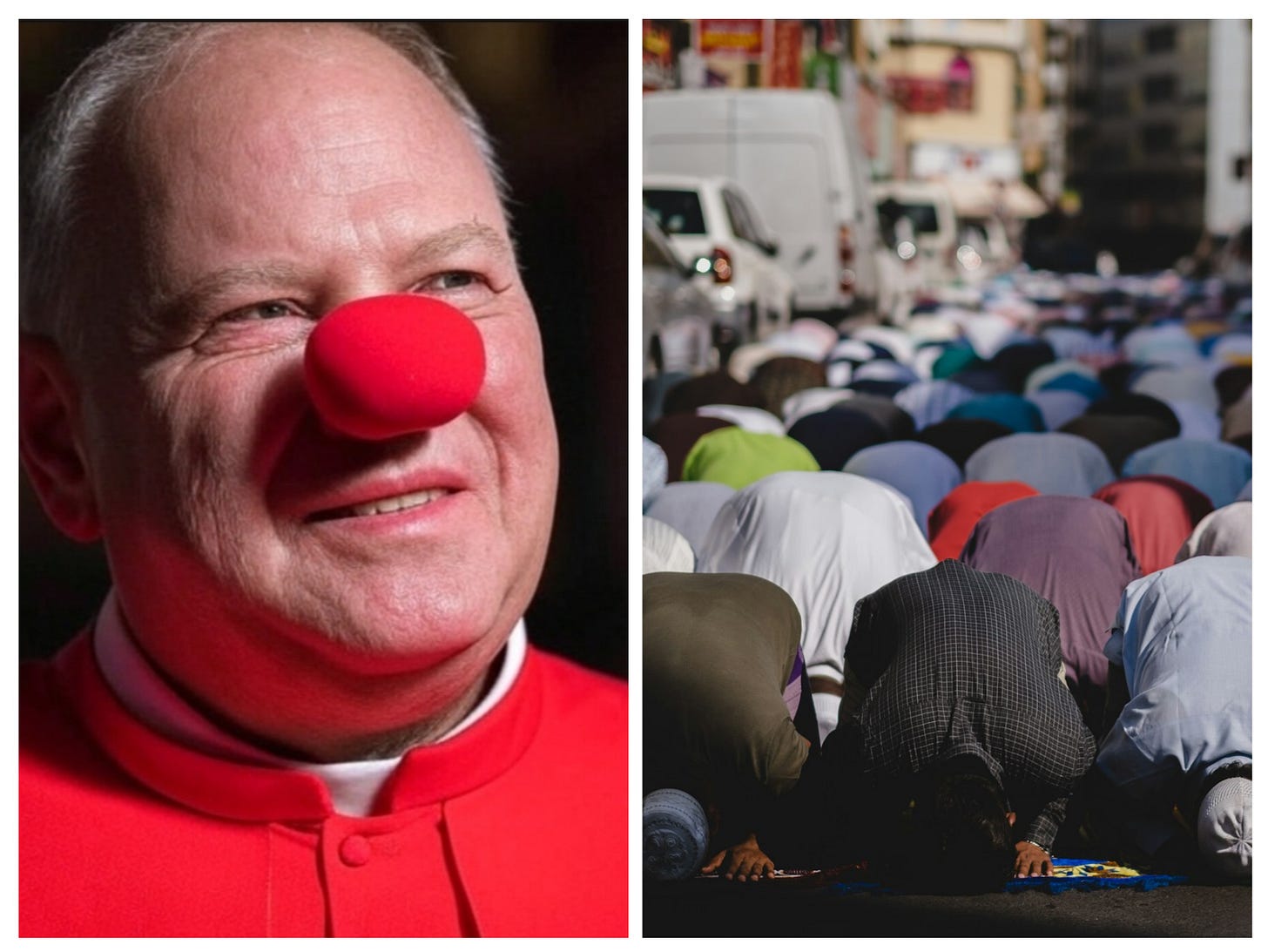

In another recent example of this troubling trend, Cardinal Timothy Dolan released a video message on February 28, referring to Lent as “our Catholic Ramadan.” Such rhetoric makes it increasingly clear that a significant portion of the Church hierarchy is actively working to promote a one-world religion, undermining the distinctiveness of the true Catholic faith.

And if anyone still doubted the agenda, arch-enemy of the Catholic faith, Cardinal Blasé Cupich posted on X earlier this week that he was “Happy to be at the CIOGC’s Muslim-Catholic Iftar in Morton Grove tonight to break the daily fast observed by our Muslims brothers and sisters during Ramadan.”. (Catholic X users reacted fiercely. One user wrote “Would you please become Catholic?” while another wrote “Muslim traditions: cool man! Catholic tradition: end it, very dangerous”. The latter is a seeming reference to Cupich's recent war on Catholics who receive the Eucharist on the tongue while kneeling.)

For those who have been led astray by the errors of Vatican II, let me offer some much-needed clarity. And before proceeding, I remind my readers of Christ’s words in Matthew 28:16-20, where He gives His Great Commission:

“And the eleven disciples went into Galilee, unto the mountain where Jesus had appointed them. And seeing him they adored: but some doubted. And Jesus coming, spoke to them, saying: All power is given to me in heaven and in earth. Going therefore, teach ye all nations; baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you: and behold I am with you all days, even to the consummation of the world.”

Notice that Christ does not command us to engage in “interreligious dialogue” with pagans and idolaters. Rather, He instructs us to evangelize and bring all people into the One True Faith—Catholicism. (But more about this later).

Likewise, Psalm 95:4-5 reminds us of the true nature of false gods:

“For the Lord is great, and exceedingly to be praised: he is to be feared above all gods. For all the gods of the Gentiles are devils: but the Lord made the heavens.”

In short, we are not called to “walk together” with those outside the faith, nor to falsely unite under a banner of vague spirituality. Instead, we must remain steadfast in the truth. As Ephesians 5:11 instructs:

“Have no fellowship with the unfruitful works of darkness, but rather reprove them.”

So, Cardinals Dolan, Cupich, and Vatican News, the call is not to embrace a false unity but to proclaim the unchanging truth of Christ. With that said, let’s begin.

The Distinct Spiritual Rhythms of Lent and Ramadan

Lent is not merely a period of abstinence; it is a season steeped in the mystery of Christ’s Passion, death, and resurrection. Rooted in the forty days that Jesus fasted in the desert (cf. Matthew 4:1–11), Lent calls the faithful to a deep interior conversion. Traditional Catholic practice emphasizes not only physical fasting but also spiritual penance, prayer, almsgiving, and acts of self‐denial that unite the believer to the redemptive suffering of Christ. The Lenten discipline is a preparation for the glorious resurrection celebrated at Easter—it is meant to purify the soul and to reorient the heart entirely toward the salvific mystery of our Lord. As such, it is both a personal and communal journey toward an ever‐deeper union with Jesus.

Catholic spiritual writers—from St. Augustine to St. Thomas Aquinas—have long emphasized that the fast of Lent is intended to awaken in the soul a recognition of human sinfulness and the need for divine mercy. It is a “desert time” in which the distractions of the world are set aside so that one may listen more clearly to the voice of God, already revealed in His Son. In this sense, Lent is inseparable from the Church’s sacramental life; it is marked by the reception of the Eucharist and the sacrament of reconciliation, both of which are uniquely Christian means of grace.

In contrast, Ramadan is the sacred month in which the Quran was first revealed to Prophet Muhammad. Its observance involves fasting from before dawn until sunset, with abstention from food, drink, and other physical needs. For Muslims, the fast is a legal obligation (one of the Five Pillars of Islam) and a means of self‐purification and heightened piety. Yet—even if the discipline of fasting may seem similar in its outward practice—the purpose of Ramadan is formulated entirely within an Islamic framework. Fasting during Ramadan is seen as a demonstration of obedience to Allah’s command and an exercise in submission (Islam literally means “submission”) to the decrees of the Quran.

While both traditions share the physical act of fasting, the spiritual content diverges significantly. In Islam, the fast is not meant to evoke a participation in the mystery of a redemptive sacrifice; rather, it is an act of self‐discipline designed to cultivate taqwa (God-consciousness) and to remind the believer of the plight of those who are less fortunate. There is no sacramental connection to a saving Passion or resurrection. In fact, the very concept of an atoning sacrifice—as understood in Catholic theology—is completely absent in Islam. Instead, Ramadan is a time for recitation of the Quran, extra prayers (Taraweeh), and a focus on following a legalistic code of conduct rather than on a transformative encounter with a living Savior.

At a glance, the two observances might seem to share certain external elements: both involve fasting, self-discipline, and a call to spiritual reflection. However, any attempt to equate these practices misses the crucial point: Lent is integrally connected to the Paschal Mystery of Christ’s redemptive sacrifice and resurrection, whereas Ramadan is embedded in a system that denies the Incarnation and the Trinity. To compare them on the basis of fasting alone is to ignore the fact that the substance of what is being celebrated—and the goal of the spiritual discipline—is entirely different. In Lent, fasting is a means of entering into the mystery of divine redemption; in Ramadan, it is a demonstration of submission to a revealed legal code.

Moreover, the communal rhythm is different. In Lent, there is a deliberate anticipation of Easter—a “marathon” of penance that ends only with the joyous celebration of the Resurrection. In contrast, Ramadan is structured as a series of daily sprints: the fast is broken each evening with a communal meal (Iftar), only to begin anew with the dawn. This pattern, while effective for cultivating discipline, lacks the overarching narrative of sacrifice and redemption that characterizes Lent.

Thus, while the two periods might superficially resemble one another in terms of self-denial, their underlying spiritual trajectories diverge sharply. Lent directs the soul toward an intimate union with Christ—the very source of salvation—while Ramadan reinforces a system of religious observance that, from a Catholic perspective, lacks the transformative grace of the Incarnation.

The Nature of God in Catholicism and Islam

Central to Catholic theology is the mystery of the Holy Trinity: one God in three Persons—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This doctrine is not merely a philosophical abstraction; it is the heart of the Christian revelation. In the mystery of the Trinity, God is both transcendent and immanent, revealed most fully in the person of Jesus Christ, who is fully divine and fully human. The Incarnation, the crucifixion, and the resurrection are the definitive acts of divine self-giving that reconcile humanity to God. These events are the foundation upon which Catholic spirituality, liturgy, and moral teaching are built.

From the early Church Fathers to the Councils of Nicaea and Chalcedon, the Catholic Church has affirmed that the Son of God, our Lord Jesus Christ, is not simply a human prophet but the eternal Word incarnate. The Holy Spirit is likewise understood to be the third Person of the Trinity, who inspires the Church and sanctifies the faithful. This self-revelation of God as a Triune Being is the cornerstone of the Catholic understanding of salvation and is inseparable from every aspect of Catholic worship, including the celebration of the Eucharist and the sacraments.

In stark contrast, the Islamic doctrine of Tawhid (the oneness of God) emphasizes absolute monotheism—a God who is utterly transcendent and indivisible. The Quran vehemently rejects any notion of God having partners or being divided into persons. The declaration “There is no god but Allah” (lā ilāha illā Allah) encapsulates this understanding. For Muslims, any suggestion that God could be understood as three distinct Persons is tantamount to shirk (associating partners with God), which is considered an unforgivable sin if committed knowingly.

The Islamic view holds that God’s nature is wholly singular and unmediated by any form of incarnation. The Quran denies that God became man, and Islam rejects the idea of a savior who suffers, dies, and is resurrected as a means of redemption. The Muslim God is, by definition, beyond human comprehension and completely separate from creation; He neither incarnates nor experiences human frailty. As such, while both Catholics and Muslims affirm the oneness of God in a nominal sense, the substance of that oneness is understood in radically different ways.

Because the Catholic Church insists on the revelation of the Triune God in the person of Jesus Christ, the claim that Muslims worship the “same God” becomes “problematic” (I am being euphemistic here).

For Catholics, the Incarnation is not an optional add-on but the very heart of what it means to worship the one true God. In Jesus Christ, God took on human flesh so that He might redeem a fallen world. This self-giving love is the source of every Christian virtue and sacrament. Without this self-revelation, there is no true adoration of God as He is revealed to us. Therefore, even if a Muslim sincerely practices fasting, prayer, and submission to the commandments of Allah, his understanding of God remains fundamentally flawed from a Catholic standpoint. He worships a God whose revelation is incomplete and whose saving plan does not include the salvific mystery of the Cross and Resurrection.

The Triune God vs. the Unitarian Allah

The Catholic Church has always proclaimed the doctrine of the Most Holy Trinity: one God in three Persons—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This is the central mystery of the Christian faith, revealed definitively by Christ Himself.

Islam, on the other hand, vehemently rejects the Trinity. The Quran explicitly denies the divinity of Christ:

“They do blaspheme who say: ‘God is Christ the son of Mary’... God is but one God: Glory be to Him: (far exalted is He) above having a son” (Quran 5:72-73).

Muslims do not worship God as Father, nor do they acknowledge the divinity of Jesus Christ. Instead, they believe in a strict monotheism that denies the Incarnation, the Passion, and the Resurrection—the very foundation of the Catholic faith.

Given these irreconcilable differences, it is incorrect to say that Catholics and Muslims worship the same God. The Catholic God is the Triune God—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—while the Islamic god is a distant, impersonal deity who denies the Son. This is why traditional Catholic theology has always rejected the notion that Islam is a true worship of God.

Historical Church Teaching on Islam

For centuries, the Church recognized Islam as a false religion. Pope St. Pius V, Pope Benedict XIV, and other popes repeatedly warned against Islam’s rejection of Christian truth. Even St. Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Contra Gentiles, argued that Islam’s understanding of God was defective because it rejected the divine nature of Christ.

However, in recent decades, the Church’s approach to Islam has shifted dramatically, so much so that it is heretical. The modern Catechism, particularly in paragraph 841, claims:

“The plan of salvation also includes those who acknowledge the Creator, in the first place among whom are the Muslims; these profess to hold the faith of Abraham, and together with us they adore the one, merciful God...” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 841).

This statement is false because it contradicts prior magisterial teaching and Catholics should reject it and its implications. While Muslims may claim to worship the God of Abraham, their understanding of God is so radically different from the Christian revelation that any claim to a shared worship is misleading.

If Catholics and Muslims truly worshiped the same God, then the Incarnation and the Trinity would be mere optional beliefs rather than the central truths of Christianity. This modern claim undermines the necessity of Christ for salvation and weakens the Church’s missionary imperative to evangelize Muslims and call them to the fullness of truth.

Traditional Catholic teaching has long rejected the idea that a mere “professing” of monotheism is equivalent to receiving the grace of the New Covenant. Rather, it emphasizes that true worship must be rooted in the recognition of the Son of God as our Savior. This is why the Church insists on missionary work directed toward non-Christian peoples: because without the saving knowledge of Jesus Christ, the adoration of God remains incomplete and ultimately erroneous. To assert that Muslims worship the same God in the same way as Catholics is to ignore the fundamental difference between natural religion and the revealed faith of Christ.

The Danger of False Ecumenism

Modern attempts at interreligious dialogue sometimes promote the idea that all monotheists are in some sense “siblings” in worshiping the same God. However, from a traditional Catholic perspective, such ecumenism risks diluting the truth of the Gospel. When the Catechism’s language in paragraph 841 is interpreted to mean that Muslims are already in a state of salvation because they “adore the one, merciful God,” it leads to an erroneous assumption: that there is no need for evangelization among Muslims. Yet, Scripture is unequivocal that salvation is found only in Christ (cf. John 14:6). To suggest otherwise is to abandon the unique claim of the Incarnation and the Cross.

Moreover, false ecumenism may invite a dangerous relativism. If we begin to assert that all monotheistic worship—even that which denies the essential truths of the Trinity and the Incarnation—is equivalent, we undermine the Church’s mission to proclaim the fullness of revelation in Jesus. The Catholic Church has always maintained that while there are “rays of truth” in other religions, they are not the fullness of truth. To say that Muslims worship the same God without acknowledging that their understanding is incomplete is to risk a form of syncretism that ultimately compromises our witness.

The Realities of Mission and Evangelization

The Great Commission (cf. Matthew 28:19–20) calls Catholics to evangelize all nations. If one were to claim that Muslims already worship the true God in the fullest sense, it would remove the urgency of proclaiming the Gospel to them. In fact, history and Church teaching alike affirm that every soul is in need of the saving grace that comes only through faith in Christ. While the Church’s language of “together with us” in the Catechism is meant to express a respect for the natural monotheistic impulse, it does not equate to endorsing a theological parity. Evangelization remains necessary, for without the knowledge of the fullness of God’s revelation in the person of Jesus, no one can attain the eternal life promised by Christ.

The Church’s insistence on the uniqueness of Christ’s revelation is not a rejection of dialogue or mutual respect; rather, it is a declaration of the truth that God has chosen to reveal Himself in a particular way. As traditional Catholic apologists have argued, if we claim that Muslims worship the same God, we must also accept that they, like the Jews, have inherited an incomplete understanding of the Creator—a view that does not grant them the salvific benefits of Christ’s sacrifice.

The Call to Holiness

Finally, the differences in our worship of God have practical moral implications. For Catholics, the doctrine of the Trinity is not a mere abstract belief; it informs our understanding of divine love, which is expressed in the self-giving nature of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This love is the source of our call to charity, forgiveness, and solidarity with the poor. When Catholics participate in Lent, the self-denial we practice is not a goal in itself but a means to participate in the saving work of Christ. The sacrificial nature of Lent—its connection to the Cross and the Eucharist—transforms our inner lives and compels us to act justly in the world.

In contrast, the Islamic concept of worship, while rigorous in its legalism and discipline, lacks the supernatural dimension of self-offering in the person of Jesus. Fasting in Ramadan, though an act of solidarity and remembrance of the needy, does not culminate in a mystical union with a suffering Redeemer. Thus, the moral and spiritual fruits that emerge from a Lenten life—renewed charity, genuine repentance, and a sacramental encounter with the divine mercy—are uniquely Christian. They bear witness to a God who is not only just and merciful but who has himself borne the sin of the world on the Cross.

Upholding the Unique Revelation of Christ

The Catholic Church has always held that the fullness of God’s self-revelation is found in Jesus Christ. While it is true that many non-Christian religions—including Islam—proclaim a belief in one God and practice acts of fasting, prayer, and almsgiving, these practices do not substitute for the saving truth of the Gospel. Lent is a time when Catholics are invited to enter into the mystery of Christ’s Passion and Resurrection—a mystery that transforms our understanding of sin, grace, and divine mercy. Ramadan, by contrast, is a ritual observance designed to enforce submission to a legalistic code, one that expressly rejects the central tenets of the Incarnation and the Trinity.

Similarly, while the Catechism’s language in paragraph 841 notes that Muslims “profess” to hold the faith of Abraham and “adore” the one, merciful God, this acknowledgment is limited to a natural recognition of a god’s existence. It falls far short of the supernatural revelation that Catholics have received in Christ. To suggest that Muslims worship the same God in the same way as Catholics is to ignore the fundamental difference between natural theology and the revealed truth of the New Covenant.

The Church’s traditional teaching, drawn from the wisdom of the Fathers and the magisterial documents of the past, emphasizes that true worship arises only from a proper knowledge of God—a knowledge fully revealed in the person of Jesus Christ. Any attempt to conflate Catholic and Islamic worship does violence to that truth. As the Church has historically taught, while other peoples may have a rudimentary or even sincere knowledge of the Creator, only in Christ is that knowledge perfected and transformed into saving grace.

In our mission to evangelize all nations, we must therefore remain steadfast in proclaiming that salvation comes through Christ alone. We must engage in dialogue with Muslims with charity and respect, yet without compromising the unique claims of our faith. To accept that Muslims worship the “same God” in a manner equivalent to Catholic worship is to ignore the transformative power of the Incarnation—a power that has redeemed the world and given us the means to attain eternal life.

May our celebration of Lent be a testament to our belief that our God is not merely the creator of the universe but the redeemer of souls—a God who loves us so much that He became man, suffered for our sins, and rose victorious from the dead. And may we continue to bear witness to this truth with unwavering fidelity.

Ave Christus Rex!

Recognise & Resist!

ALSO READ:

How to deal with a wolf in shepherd's clothing

Catholic Church or Modernist Circus – St. Bellarmine settles the argument

Beyond the “Early Church Received in the Hand” argument and that St. Cyril quote

A letter to my neo-Protestant “Catholic” friend – Why tradition and orthodoxy matter

A T-shirt or bumper sticker that says “I gave up Ramadan for Lent” would get the message across quickly.

Amen